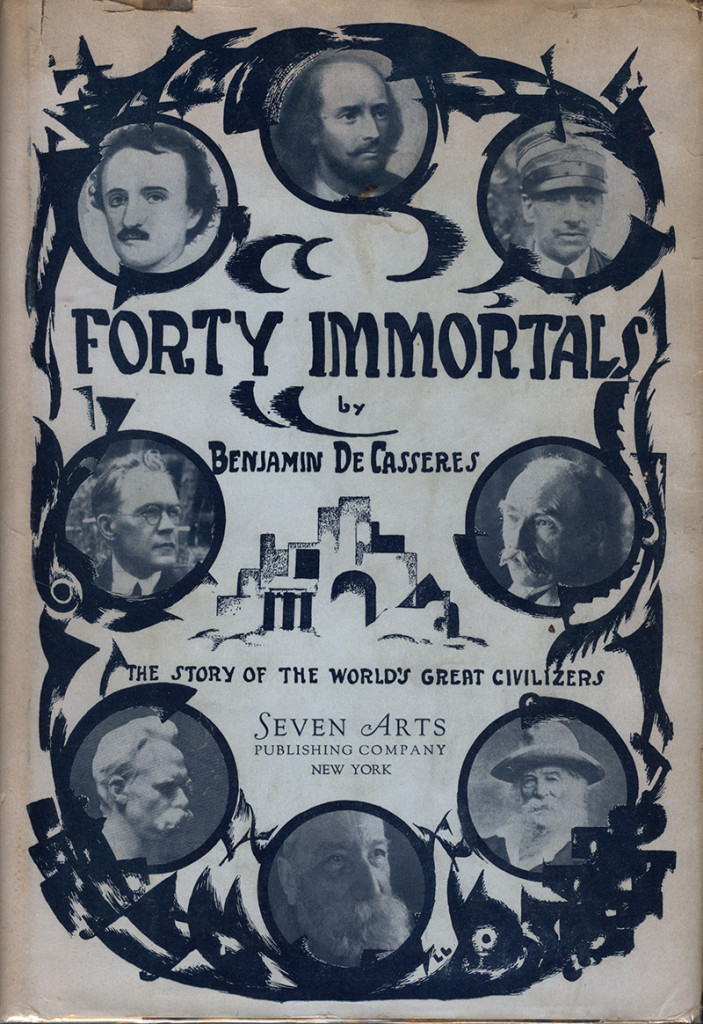

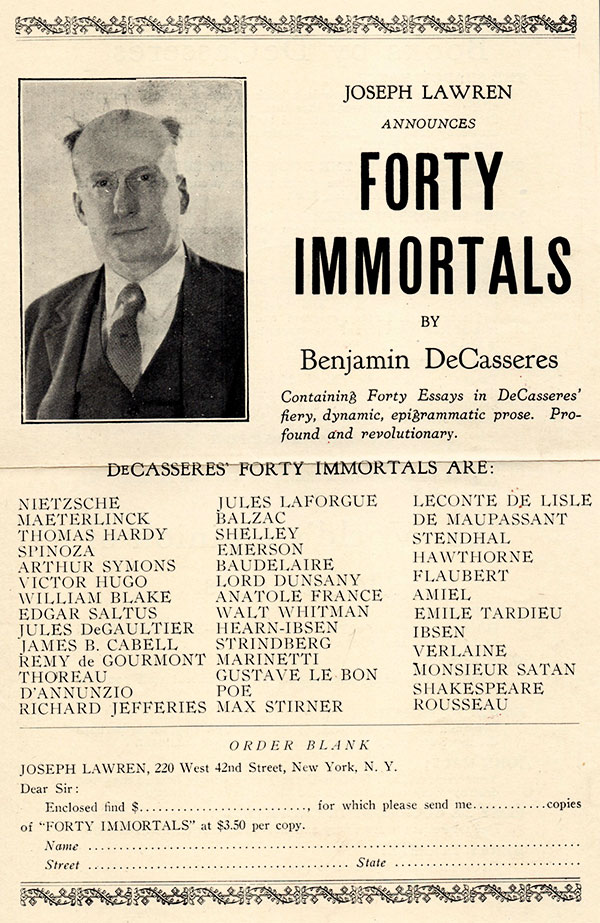

Publisher: Joseph Lawren/Seven Arts

Publisher: Joseph Lawren/Seven ArtsYear: 1926

Pages: 371

Table of Contents

Nietzsche

Maeterlinck

Thomas Hardy Spinoza

Arthur Symons : An Impression

Victor Hugo : Thunder-God

William Blake

Edgar Saltus

Jules De Gaultier

James Branch Cabell

Remy De Gourmont : After-Man

Thoreau

Gabriele D’annunzio

Richard Jefferies : A Pagan Mystic

Jules Laforgue

Balzac: The Clumsy Titan

Shelley

Emerson The Mystic-The Individualist-The Sceptic And Pessimist

Baudelaire : Ironic Dante

Lord Dunsany

Anatole France

Walt Whitman

Hearn-Ibsen

Strindberg

Marinetti And Futurism

Gustave Le Bon

Poe

Max Stirner : War-Lord Of The Ego

Leconte De Lisle

The Malady Of De Maupassant

Stendhal : Geometrical Don Juan

Hawthorne : Emperor Of Shadows

Flaubert : Chemist Of Illusions

Amiel

Emile Tardieu : Historian Of Ennui

Ibsen

Verlaine

Monsieur Satan

Shakespeare

Rousseau

Order Form

This order form was found inside a review copy of Forty Immortals that was from the library of Baltimore Sun reporter T. Denton Miller.

Excerpt

EDGAR SALTUS

Somewhere in that Never-Never Land of Lord Dunsany there is a dusty road that stretches from Here to There. Along this road there trudges a figure. From the fact that his clothes are ragged, that his shoes are split and that his face is a gray dead heaven in which are imbedded two big, black stars weltering in light you may infer that he is a Poet.

A Lady, with a nimbus and a wand, incorporates herself out o’ th’ air and walks besides the Superfluous Being. She is Fame. You may know that by the ironic grin in her eye.

They talk. And when Poet and Fame talk the fairies and the demons listen and the solid old earth becomes such a garden as one sees in the Kingdoms of the Pipe.

But the upshot of the fable is (and I am not telling the story strictly on the level) that Fame gives the Poet a rendezvous—behind his tombstone one hundred years from date.

Saltus! Saltus! In what storied urn of memory reposed the word? In what sarcophagus of the past had I laid that verbal corpse? In what penetralia had I met the man with that name? At what Petronius feast of intellectuals had I clinked glasses with that being?

The bandalettes slipped from a hidden face and the blood came surging back into petrified arteries, and eyes that I thought sealed opened wide, and great jewels fell from them that sang in words and formed themselves into daggers called epigrams.

And Edgar Saltus rose out of his Pompeii. Well, as a matter of fact, he had only been summering in Oblivion.

There are three mysteries in American literature —the appearance of Edgar Allan Poe, the disappearance of Ambrose Bierce and the burial alive of Edgar Saltus. It is fairly certain that the latter was pretty comfortable in his grave; and it is still more certain that he begemmed his coffin with prose poems scratched into the pine wood with worms—worms, which are the epigrams of the sod. Then, too, without doubt, he had his Théophile Gautier with him, his Baudelaire, and was fed from the amphoræ of those two angelic ghosts, Leconte de Lisle and Villiers de l’Isle Adam.

Here is an American that knows his language, that knows the creative and mystical power of words, that knows the phrase that kills and the sentence that is winged. As exotic as Poe and Lafcadio Hearn, his books should be called Pomp and Purple.

A lyrical intellect, an implacable pessimist, a sublime snob, he stands aloof and alone in his work. His contempt and disdain of “merely human” things is beautiful. It is a gesture toward the Infinite.

This accounts for his unpopularity. He will have none of the mob. The sweat of everyday life to him is just sweat. The life of the poor is not a drama; it is a disease. The poor and the weary laden exist no more for him than they did for Emerson.

Whatever is not genius is dross. Whatever is beautiful is right. All life aspires to fiction. Humor is an attribute of God. Life itself is the conundrum of a Jester.

His books take apart the mechanism of the quick. When he wrote The Philosophy of Disenchantment he was crowned by some one as “the Prose Laureate of Pessimism.” All is illusion in the worst of possible worlds—“so let us live in Paris.” The characters in his novels of New York life move like hallucinated automatons. There is a hero in each book—Mephistopheles.

Saltus is so great that he is unpleasant. He is as unwholesome as truth. He sees so far that his brain cells must be made up of telescopes that gods in the Fourth Dimension use to study the humans in the Fifth Dimension. He is as uncanny as the thought of immortality. And above all his work hangs the irony of Brahma.

His Tristrem Varick is the greatest novel that ever came from the pen of an American—a fable, a philosophy and an enormous chunk of life. It is a tale of the pursuit of the Ideal by Man—and the end is a badly lighted room in the Tenderloin police station.

He is on intimate terms with the gods and pals with the predestined criminals of all time—from Cain to the Borgias. He plays hide and seek with Nero, Tiberius and the Kaiser—he wrote this in 1906 in a chapter on hyenas (the hyenas are Caligula, Attila, Tamerlane, Ivan the Terrible & Co.):

“…The German Kaiser. Not long since somebody or other diagnosed in him the habitual criminal. We doubt that he is that. But we suspect that were it not for the press he would show more of the primitive man than he has thus far thought judicious.”

But it is because of his style that he will live. He has said nothing new—because there is nothing new to be said. His brain is as old as Buddha’s or that of the author of “Ecclesiastes.” His style is the measured tread of his wisdom. His sentences are cut from the jewelled heavens in which he lives. His words drip into the next paragraph and form pools of images. His crescendos flower in the air, and the flowers remain there, frozen gardens. One feels him moving behind the page like a pontiff behind a huge, swaying curtain. There is no creak, no noise, no jolt. He passes imperceptibly from Zeus to Brahma, from Brahma to Amon Râ like a sun-walker shod in ether.

The genius of Edgar Saltus is his masterly insincerity. He doesn’t believe in himself, in the people he writes about, in the world he depicts, in you or me, or anything. He is a balancer, a juggler, a Houdini of phrases, a Gargantuan Capocomico who balances the Taj Mahal on his nose, the Alhambra and St. Peter’s on his skull and tosses buddhas and bonzes, bibles and sultans in vast circles like eggs, precisely sure of never missing one, while the orchestra thunders a Valkyrean battle charge toward the Gates of Nowhere—an orchestra conducted by the Furies.

But only the profoundly sincere in spirit can enter the Kingdom of Insincerity. The Wildes, the Chestertons, the Hunekers, the Anatole Frances, the Shaws and the Renans are to the manner born. They may play battledore and shuttlecock with everything because they are everything—and nothing; they have the frivolous, ironic gayety of Nature, that emits swallows and earthquakes and bluebells and pests and lunatics and fairies and passes on with a sublime indifference.

Their imitators come along; then we see an elephant trying to play butterfly; Bottom doing Puck’s tricks. Insincerity is the final sense of humor—it is the laughter of the nihilist from the chimney of the House of Life, where he plays with the tomcats, the stars and the blind bats of chance.

Neither Moliere nor Balzac sat in the Academy. Edgar Saltus must remain our forty-first Immortal.

Reviews

(the following has been slightly truncated)

I have just been reading, in his book entitled “Forty Immortals,” the poems of that flaming soul, Benjamin De Casseres.

I say “poems” deliberately, for if imagination be the very heart and magic of poetry, in few places may it be found in more gorgeous abundance than in these forty essays. De Casseres is at once a high-power microscope, giving access to the pits of psychic mystery, and a gigantic searchlight, sweeping with its fan-ray the outermost walls of the cosmos. In his terrific lines are all that man knows and most of what he has imagined. In these pages, Wisdom passes out into the night of the unknown, and Science is a firefly, sparking fitfully in the tomb we call the universe.

But first of all and above all, he is a poet, and his paragraphs prove, more conclusively than any others that I have read, the dividing line between prose and poetry. The form may deceive the eye, but never” the sensitized brain. Let me adduce for example a passage from his magnificent summing up of that master-mind, Benedict de Spinoza, setting it to lines of free-verse, though indeed but little free-verse has this sinewy suppleness of rythm…

De Casseres is supremely our greatest epigrammatist. No such blinding brilliance ever before went from brain to paper…

I often wonder what the mouse-grey school of literature will think of this Play Boy of the Cosmos…

It is its beauty, not its wisdom, that will make “Forty Immortals” immortal. In an age too precocious for play and too cynical for pure beauty, De Casseres has dared to give full rein to his imagination and ventured into the realm of sublimities. Nor is it the adventuring of a neophyte, for he can meet the devotees of ugliness on their own ground, and, his pen lifted as a wand against the mirage of Time, turn as easily as they its apples of Sodom to the dust from which Time has arisen. He is at once child and sage, Ariel and Mephistopheles, and my notion that he takes too seriously the froth and flatulence of mysticism may be itself a delusion. His is a wisdom that never tells all it surmises.

-George Sterling

June, 1926

2 thoughts on “Forty Immortals”