I

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF CARICATURE

CARICATURE is the intellect of art. As music, painting, and poetry are records of life conceived emotionally, caricature is a record of life conceived intellectually — hence satirically, paradoxically, comically. It is like an eye the retina of which holds only the ribs of a&ion, the fleshless muscles of attitude.

As irony is the supreme of philosophy, caricature is the supreme of art. Life begins in an Eden and ends in a Brocken of discords. The evolution of the individual mind is from belief to spite, from the naive and pasty vision of a Bernardin de Saint-Pierre to the withering sneer of an Aristophanes. The caricaturist vision is a vision from the very apex of mental development. It laughs at men with the brutal laugh of God. Its jest is as keen as that jest we call death.

Like the poisonous humor of Rabelais, Cervantes, Heine, Jules Laforgue, the caricaturist carries in his soul the fatal smile. This smile is mute in Cappiello, brutal in Rouveyre, fantastic in Sem, inexorable in Fornaro and murderous in De Zayas. It is born on the frozen summit of sensibility. A sigh congealed in the blood of the brain will sparkle like a diamond — and cut like one.

It is a mistake to believe that a caricaturist must necessarily draw caricatures. All those who see life as an absurdity, as something fantastic, as a stupendous Olympian jest, a sport organized by the Immanent Ennui ; all those who see life as a mixture of diabolistic humor and mystical vaudeville are caricaturists, whether their names be Shakespeare, Cervantes, Heine, Fornaro, Sem, De Zayas, or Anatole France.

Every mind who faces boldly the hidden Dramaturgist of existence and trills a tra-la-la in its ear is a caricaturist. It is the crack in the Urn of Existence—this brain-chuckle. It is a poultice of ice laid over the heart of drooling sentimentality. This tragic, this bitter, this fatal smile on the lips of Caricature ! It is a strange hieroglyphic from a hidden wisdom. It is an eccentric fata morgana that plays above the graves of reputations and discrowned celebrities. It is the gibbet of all the follies and vanities of existence. It is born of the cynicism of God itself.

And it is because of this that there is something of the macabre, something chilling, something frightful in all caricature. It is an art for the few, for the connoisseurs of life. It is an art from which paunchy, heavy-mammelled Complacency flees as from a genius. It is an art that the sleazy bourgeois mind looks on as a blasphemy—that bourgeois mind, eternal revenant of preestablished stupidity ! Sacrosan& pig around whose trough Flaubert and Heine chanted their ironical paternosters ! But caricature wounds no more than nature does, and it is no crueller than life, and is not as frightful as the hypocrites’ paradise that is called the social system.

The caricaturist has that touch of the satanic in him which redeems him from the pestilential morality and sanity of the work-a-day world. He is impersonal, disenchanted, a Nietzschean. That satanic touch which lies at the basis of his art is something akin to that cold, intellectual smile that lago threw on the corpses of Othello and Desdemona. It gnawed at the brain of Balzac till it crumbled. It put Swift on a throne of ice. Disembodied, the satanic spirit that fastens on the mind of the caricaturist is the spirit of Circumstance, the immutable gray eye of Fatality. It was the firefly with the wintry flame that encircled the head of Orestes and Oedipus, Napoleon and Edgar Allan Poe. It is the invisible satyr in worlds and destinies, the star in the forehead of Lucifer, the cold, bethlehemic light hovering over the manger of geniuses destined to strange Gethsemanes and pensive Calvaries.

Every caricaturist was once an idealist — if not in his youth, then in some previous incarnation. For him the slow evaporation of ideals and their condensation into nebulous comic visions; the slow massacre of brazen hopes ; the murderous concussion of Will and Reality. Here is the psychological root from which is born that sadic, vengeful smile, that guffaw in hell. The Ideal — of which the caricaturist becomes the eternal enemy — is a vague clarion-call sounding from impossible summits. The sense of the ridiculous forever muffles it. Chimera is become a passionless, smiling Sphinx. The ironic, the satiric, the caricatural is the final mental concubine of the disenchanted. The oval face of Grief is at last touched to a smile by that transfiguring chrism. The legioned visions of impenitent minds cannot advance beyond that unarithmetical grin. On that tragi-comic Horeb one sees men as they are.

II

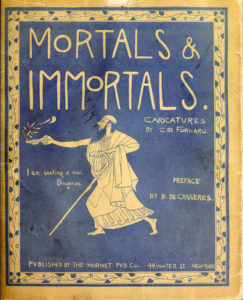

FORNARO AND HIS WORK

THE CARICATURES of CARLO DE FORNARO are entirely different from anything we know. They are absolutely original in their method and viewpoint and reflect the personality of the man. There is no invention, no pose, no affectation in his work ; it is an art that springs directly from the subconscious nature of the man. They reflect a manner of feeling more than a manner of thinking, which is not to say that his work is not intellectual. The brain

feels as well as thinks; it has its emotions as well as the heart. It is still an open question whether there is any such thing as thought at all. What we call a thought is merely a certain manner of feeling about a thing translated into an image or a word. Fornaro feels with his brain. His caricatures are the record of that feeling.

His work is the philosophy of the concrete. Each figure is complete in itself. Each pose is

definitive, struck off firmly, positively, inexorably. Each caricature is a dogma of perception. “My truth is the truth; there is no other truth” might stand as the metaphysical formula to base his art. He is not related to any one else. He is more Anglo-Saxon than Latin, more artistically brutal than delicate, though sometimes in some of his caricatures one catches a sly and mordant politeness deeper than the frank contempt of Sem.

The evolution of his art in the last ten years has been toward a greater simplicity. With a

single stroke he can focus a characteristic; a single dot reveals a thought. The caricature of

Theodore Roosevelt is an extraordinary piece of work, as is that of Senator Bourne. Here character is reduced to geometrical lines. Fornaro and Picasso have found the secret of the straight line, the poetry of logic. It is the absolutism of Spinoza applied to art.

The caricatures in this book are literature. They are a record of the men of the hour. They are a composite of America. Divine the secret of these caricatures and you are at the heart of America’s secret. The soul of it all is the Practical. And Fornaro, because he is of another

people, has divined this. The United States is giving us the romance of the Real. These faces, these forms are the epiphany of the practical, the utilitarian. Here are the Voyagers in the new Western sky, the Vikings of giant corporations, the Samsons of Wall Street, the butter-mouthed orators that make our laws and shorten our incomes. It is a saga of the West in black and white. It is real literature, great literature.

The face is the palm of the mind, and Carlo de Fornaro is a palm-reader. Before the ideal—the innocent enough looking Trojan horse wherein there is secreted a savage, starving, murderous horde — he plays Merryandrew. Before the hierophants of seriousness he squats satyr-wise and pipes a merry ditty. Civilization—the great crime against nature — has perverted mirth. Puck is dead. The daily newspapers laid on one another for a single year would be a palimpsest of unimaginable humbug. The work of Fornaro in its essence, like that of De Zayas, says Oh, go to!

It will be noticed that there are no women caricatured in this book. That is quite proper in America, for when we speak of women we are either satyrs or asses.

I peered into the face of the creator of all things and I saw therein indifference over which there had come the patina of irony ; and I peered into the face of Satan and I saw therein irony over which there had come the patina of ennui; and I peered into the faces of the caricatures done by Fornaro and I saw hypocrisy over which had spread the patina of power.

BENJAMIN DE CASSERES.