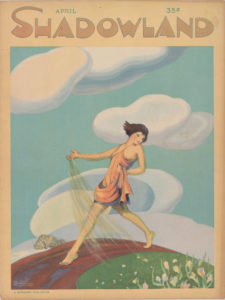

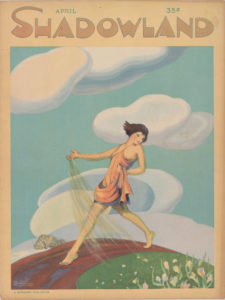

The following was published in Shadowland magazine for April, 1922.

De Maupassant: Vagabond Faun

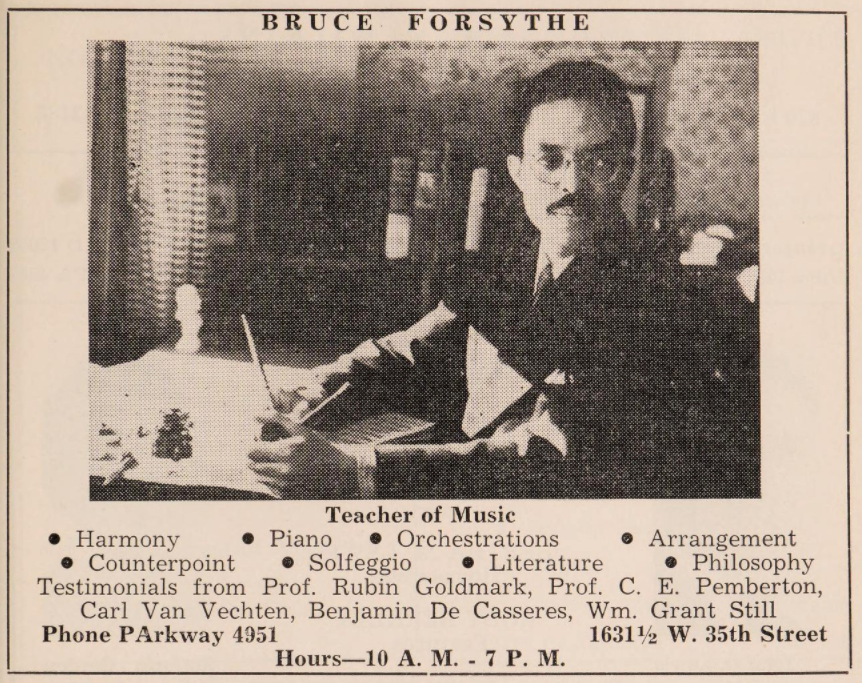

by Benjamin DeCasseres

GUY DE MAUPASSANT was a strange ethereal beast, a satyr at sprawl amid the lilies, a star-ranging butterfly meshed in compost. His written works are the de profundis of a great spirit, a miserere chanted in a crypt. There is everywhere in his works the record of a great agony, a ceaseless conflict with devils, a sincerity pitiless and pitiful. His poetical fancy, as elusive as the sheen on the waterfall, bruised its gossamer envelope at every turn against some nameless Shape. This dread shadow blocked his path like a sewer-rat crouched on the path of a running child.

GUY DE MAUPASSANT was a strange ethereal beast, a satyr at sprawl amid the lilies, a star-ranging butterfly meshed in compost. His written works are the de profundis of a great spirit, a miserere chanted in a crypt. There is everywhere in his works the record of a great agony, a ceaseless conflict with devils, a sincerity pitiless and pitiful. His poetical fancy, as elusive as the sheen on the waterfall, bruised its gossamer envelope at every turn against some nameless Shape. This dread shadow blocked his path like a sewer-rat crouched on the path of a running child.

What is the secret of these souls that come into life with a sure knowledge of life’s worthlessness? Where are those secrets learned? On what worlds of magnificent possibilities had the spiritual eye of Flaubert, De Maupassant and Schopenhauer gazed that with the sure instinct which urges the average mortal to take his pleasure bade these men spurn what is here? What profound mystery lies behind the possession of powers that by no possibility can be used on this early stage, constructed for the marionettes of the instinctive, the, puppets of the sexual and the stomachic! From what mystic Utopia had De Maupassant fared that this earth seemed to him little else than a scudding ball of ordure and the days of man hierarchies of the petty? With what gods had he conversed that the speech of mankind was to him ape-chatter?

The great cynic and the great idealist—and a cynic is an idealist temporarily bankrupt—belong to an order of their own—and that order is not the earth-order. Their souls in some fine foretime, unfettered by inelastic flesh coverings, had hurtled thru super-lunar spaces in the ecstasy begotten of unlimited power ; a pause, a misstep, and they are immured in clay-wrappings and are condemned to live and record. Ignorance makes for happiness, and limits that the crowd believes to be ultimates, whether they be physical, intellectual, or religious —limits at which a priest or lawyer has affixed a flaming sword —numb the will and generate that easy acquiescence in things as they are. “Happy are those whom life satisfies, who are amused and content,” sighs De Maupassant. For him nothing, changed—the days were monotones strummed upon catgut. When he Went into the street, the same man met him who met him the day before; their gestures were the same; their faces differed from one another only in the degree of stupidity which the flesh records registered; they shuffled, they haggled, they drank, they ate, and haggled again, and, when the shadows of the sun grew long on the Parisian boulevards, they shambled, shuffled home by the million. “And for this, man was born?” asked the great French pessimist, brooding en the mob’s docility, its unchangeable stupidity, its indestructible illusions, its adamantine asininity.

With a diabolical prankishness he liked to peer at the people at play, at work, at .prayers ; dissect their virtues, which he knew to be masks for their sinister lusts ; wonder at their clinging to life like soft mud to a cart’s wheel—and tho the wheel and its endless gyrations flattened them to a slimy ooze, still they rebelled not ! He wondered at that great Policeman of the people whom they called God, with his Scotland Yard methods and Puck-like pranks. De Maupassant’s contempts were built up of impotent rage and a consciousness of his own transcendent vision—a vision that gave us’ the finest short story in the world—”The Necklace.”

Like Amiel, his soul was constantly gnawed by a consciousness of the Infinite—not that concept of the Infinite that terrorizes, but the Infinite split into infinite shadowy goals that some minds pass before they have begun the race, To these minds the infinite is a process, not a thing; not the water that runs thru the hand, but the spirit of elusiveness that animates the disappearing-reappearing, tantalizing flow. Mentally, they are inversions, not perversions. The commonplace, everyday being works from the layers of the concrete up to the abstract; his idea of time is founded on the clocks he has seen; life has first to batter his pate to a pulp before he can apprehend the idea of universal pain. But the order of beings of which Guy de Maupassant is a type evolves in a way that is diametrically opposed to the average mortal. Their souls at birth are a conflux of ideas, and they burrow their way down from the ideal to the real. They interpret, translate and create. The earth-child grubs.

De Maupassant was like an ant that has crawled accidentally from the light of day thru the air-hole of a boy’s rubber ball, there in the interior to spend his days meditating on the dark. The meanness of the universe astonished him ; the battledore and the shuttlecock of the planets was an insane pastime ; the music of the spheres was cosmic yawp. “We can at least be good animals,” he exclaims ironically. “My body is real, my lusts are pleasure-pregnant. There is always room for the lowest. Loaf and take thy sport, dear body. I feel thrilling within me the sensations of all the different species of animals, of all their instincts, of all the confused longings of inferior creatures.” Not as a poet does he love the earth, but as a beast. Like a pound where on certain nights the spirits of a myriad throttled beasts revivify and with snarl and claw and blood-smeared fangs live over their dead earth-selves, so did De Maupassant at regular intervals fling open the door of his nethers and lead forth the caged sleek couriers of our past and glut them at the sties of pleasure. But he writhed in his raptures, and his pastimes were crucifixions.

It is curious that what is beautiful has so much evil in it. It is often thru “sin” that spirituality is born, and what finer virtue halos the soul than the consciousness that it is always possible for us to do evil in thought and be the secret bridegroom to the throttled lusts which we style our ideals ? De Maupassant realized the beautiful thru the evil in him. He molded the rich fungi on his brain-walls to immortal little waxen images and pinched his heart until it gave out music—music as evil and beautiful as truth. Philostratus tells us of a dragon whose brain was a blazing gem. Such a brain inhabited the body of the man who called himself “a lascivious and vagabond faun.”

The grotesque cravings of this man ! He shivered in horror at the antique, ever-recurring whirr that shook him from his slumbers. Each day he wished to be his last and first. He would have had Death weave her dark mantua around him each night that his eyes should rest each morn on something new. Poetry, art, music, bring us nothing, for they merely record ourselves ; they are the lengthened shadows of dwarfs. A new series is needed to recreate the soul staled by its very uselessness. Not new worlds, but a new world, is the goal of the distraught. Art is a stained image, experience is like a romance with the woman left out, and pleasure is but an opiate for despair.

We are two. Children that spend hours talking to themselves are aware in a dim way of the duality of the individual. In each soul there slumbers this other self, this shadow of the soul that waxes and wanes with our consciousness. It is the house of defeated dreams, the shadowy rendezvous of our uncoffined hopes ; a weird specter of the Great Desire. There are kenneled in the breast of this alter ego the women we never possessed, the gigantic deeds we never did, the “best” we have left undone, the worst we have done, our abrogated acts. Builded day by day, in slumber and in day dream ; builded of infinite trifles, this Horla, this vast phantasm of a self that never was diswombed unto reality, is the custodian of an endless, inutile past. It holds for ay our brief against the Eternal and mocks us with its demon eyes and its reproaches, half-wail, half-sneer.

De Maupassant, from the vats and the slime-pools of despair, conjured up his double and made of it a living, palpable thing of terror. Like the apparition that appeared to Markheim, in Stevenson’s perfect story, it was both the scorekeeper and umpire of his soul. It visited him in the dead of the night and woke him with the dull thump of its ebon knuckles on his heart. “It spoke to me in a short’ whisper of all that my insatiable, poor and weak spirit had touched upon with a useless hope, all that toward which it had been tempted to soar, without being able to tear asunder the chains of ignorance that held it.”

Is this half-created thing which each of us has in him, this unmanageable It of our own fabrication, a promise or a retribution ? Come with it airs from heaven or blasts from hell? Is it the shadow of a real Higher or a sooty smoke shape of the past ? In the stupendous conflict of opposing wills which we call society, where our fine hopes are frost-killed or done to death by main force, there is always a reserve of force—or is it a residuum? And that same conflict that is repeated in miniature in the cells of the individual has bred its reserve or residuum. We call it alter ego, Horla, doppelganger, our better self, our worse self ; is it reserve or residuum ?—unused power or slime?

Tho one of the intellectual elect, one who knew the pain in things before he experienced life—a seer who knew that the Veil of Isis was only a drab’s dirty kerchief—the presence of the squalid, the distorted images of beggars, the obscene poverty of the masses, gave him pain for which he could find no cure. The banal, the trite, the garbage dumps called cities, tortured him and drove him to his boat, to the seashore, to long mountain tramps where he tried to shut out the horrible things that spawned in Paris —the City of Light and Darkness. He was visited at such moments by strange penitential scourgings that he should be among the “fortunate.” Why was he not yonder beggar or that lame thing that was a woman? These street pictures stood out year after year in his brain in an undying protest against himself. Of misfortune he made an image as of terror he made a Thing.

We have our judgments—but they are never final. Each brain is but an angle —no one has yet lived who has seen the Whole. Where does the beast in us end and the beatitudes begin? Can the dreams of the spirituel be separated from nerve-centers? Track spiritual impulse to its lair and we find ourselves in a den of beasts ; track the sensual impulse up the steeps of the ages and we find ourselves lost in psychic mists. Is the soul of a man a pallid, manacled, protesting, guest-prisoner at the feasts of the flesh, or are the feasts of the flesh the only banquet in which we shall ever participate? What a contrast there is between the tiger pacing his cage in the zoological gardens and that great blonde beast.roaming the forests for prey ! This transformation in the world of men is called “spiritualizing the instincts”—a contradiction in terms. The subjugation of the majestic is the occupation of mediocre minds and socialistic puritans. Impotent Modernity ! The race today has no character. We are lame in our lusts ; our spirit has one watery bloodshot eye, and from our armpits we have grown hooks so that we may better hold to that which we, ragpickers and old do’ men, have won in the refuse heaps of civilization.

The back-alley Captain Kidds, the buccaneers of ash-heaps, the trumpeters of half-and-half—that is, Respectability—will always decry from their vast Sunday heights the man De Maupassant, who was what he was to the hilt, who when Beauty called him gave himself up to her in his entirety, and when the Beast snarled cried, “Here am I,” and when the Intellect levied on him her tribute rendered up his brain-house and its treasures to her demands

GULLIBUS:—But if your theories prevailed what would become of the race?

GULLIBUS:—But if your theories prevailed what would become of the race? GUY DE MAUPASSANT was a strange ethereal beast, a satyr at sprawl amid the lilies, a star-ranging butterfly meshed in compost. His written works are the de profundis of a great spirit, a miserere chanted in a crypt. There is everywhere in his works the record of a great agony, a ceaseless conflict with devils, a sincerity pitiless and pitiful. His poetical fancy, as elusive as the sheen on the waterfall, bruised its gossamer envelope at every turn against some nameless Shape. This dread shadow blocked his path like a sewer-rat crouched on the path of a running child.

GUY DE MAUPASSANT was a strange ethereal beast, a satyr at sprawl amid the lilies, a star-ranging butterfly meshed in compost. His written works are the de profundis of a great spirit, a miserere chanted in a crypt. There is everywhere in his works the record of a great agony, a ceaseless conflict with devils, a sincerity pitiless and pitiful. His poetical fancy, as elusive as the sheen on the waterfall, bruised its gossamer envelope at every turn against some nameless Shape. This dread shadow blocked his path like a sewer-rat crouched on the path of a running child.

THE UNCONQUERABLE JEW

THE UNCONQUERABLE JEW